Public Service Trusts: a solution to the crisis in local government finances?

In Leicester, adventure playgrounds used by children in the school holidays are being closed. In Hampshire, funding for mental health wellbeing services has been cut in half. In both the London Boroughs of Havering and Newham, the councils have announced they are unable to fund Christmas lights for 2024. Sunderland had 11 council-run libraries in 2016, but today just three are left.

All these visible signs of decline are the direct result of the crisis in local government finances. They are contributing to a general sense that things are getting worse in our neighbourhoods, high streets, towns and cities.

The whole local government finance system is creaking. Since 2018, seven councils have declared effective bankruptcy by issuing Section 114 notices. A total of 18 councils are relying on Exceptional Financial Support from central government in the 2024-25 financial year. By 2029-30, councils could face an £11bn funding shortfall.

In Demos’s new paper, Beyond the Sticking Plaster: A vision for long-term reform of local government finances, we argue that structural reforms are needed. We propose creating what we call ‘Public Service Trusts’: the rest of this article sets out why we think these could be a solution to the crisis in local government finances.

Councils’ spending is dominated by demand-led high needs services

In our paper, we identify a category of services which are ‘demand-led’ and relate to supporting people with high needs. There are four specific policy areas in this category which are putting severe pressure on local government finances:

- Adult social care, where demand is rising due to an ageing population and more ill health in the working-age population

- Children’s social care, where costs are rising partly due to private providers making excess profits

- Homelessness and temporary accommodation, where councils are picking up the bill for the fact that there are a record-high 117,000 households, including 150,000 children, living in emergency temporary accommodation

- Support for children and young people with special educational needs and disabilities (SEND), where demand has been increasing rapidly. Local authorities already hold around £3 billion in debt related to SEND, which central government is currently allowing them to hold off balance sheets via a Statutory Override. Without this measure, more councils would be forced to issue Section 114 notices.

All these services share two characteristics: they support people with high needs or in difficult circumstances, and they are ‘demand-led’ – that is, typically there are national eligibility criteria which set out what a local authority must do, for example, if someone is homeless, regardless of the cost or the local authority’s budget.

Councils’ spending is increasingly dominated by these demand-led high needs services. Across all local authorities, adult and children’s social care combined accounts for 67% of spending. London boroughs collectively spent £4 million every day last year on temporary accommodation.

Local authorities are also unable to raise significant revenue, because central government controls most aspects of council tax and has imposed a limit of a 3% increase without a referendum (a further 2% is permitted specifically for social care).

This leaves councils with no choice but to cut other services, from libraries to Christmas lights.

In our paper, we argue that for too long local government has been treated as the ‘delivery arm of central government’. We propose a new vision which we call liberated local government, which would enable councils to focus on improving their local areas and responding to the priorities of local residents.

To achieve this vision, we suggest creating Public Service Trusts to take responsibility for funding demand-led high needs services.

Creating Public Service Trusts

Demand-led high needs services, like social care, are essential public services which support some of the most vulnerable people in our society. However, currently each individual local authority bears the burden of risk for funding these services. This financial structure also enables central government to pass new legislation, like the Homelessness Reduction Act 2017, which mandates councils to provide additional services without giving them adequate funding.

We therefore propose that central government should consider creating new Public Service Trusts (PSTs) to deliver demand-led high need services such as adult social care. Public Service Trusts would be directly funded by central government, not by local authorities. They would be strategic organisations, not delivery organisations, akin to the Integrated Care Boards (ICBs).

This would see fiscal responsibility for demand-led high need services shift from local to central government, where risk can be more effectively pooled, and where the resources available to the central state mean that it is possible to meet demand in the long term. Services would still be delivered at a local level, where the expertise and insight of local councils can improve outcomes.

What services would Public Service Trusts deliver?

The sequencing of services moving over to the responsibility of a local PST would be a matter for consultation. Initially, PSTs could take on responsibility for adult and children’s social care across a local area. Central government would provide funding for adult and children’s social care directly to the PST and be responsible for any deficits that emerge. The PST would then fund adult and children’s social care provision locally, commissioning local authorities, VCSEs or private providers as part of a long-term plan. Financial responsibility for preventing homelessness and for the SEND system could also be given to PSTs, as these share similar characteristics to adult social care and children’s social care: they are demand-led and are mandated by central government.

How would Public Service Trusts be governed?

A PST would be governed by a strategic Board including representatives of the relevant local authorities, Combined Authority (if applicable), and other public services such as ICBs, schools and policing. Over time, as more services were integrated into the PST, more service providers could join the Board (for example, probation services could be brought into the PST). Ensuring that local authorities (and a Combined Authority if applicable) are able to influence the PST’s decision-making is important for local democratic accountability, while including other public services is designed to facilitate place-based collaboration. Local authorities would also be involved in the appointment of Chairs of PSTs.

How would Public Service Trusts be held accountable?

Financially, a PST would be like an NHS Trust: accountable to central government for how it spends money overall, but with flexibility to choose how to spend that money. If it does not have enough money to meet demand within a financial year, there could be a system to enable the PST to publicly request additional funding to meet demand. The National Audit Office, or another body, could be given responsibility for inspecting spending and value for money.

As central government will be providing the funding, accountability to the centre will also be needed: for example, CQC and Ofsted could be given responsibility for joint inspections of how PSTs are commissioning services and collaborating with other local services.

How can Public Service Trusts help to reform service delivery?

Public Service Trusts can provide a platform for reform of services. Currently, the crisis in local government finances makes reform extremely difficult. Many local authorities are understandably focused on finding cost savings to stay afloat financially, but this makes it almost impossible to find the necessary resources to commit to longer-term reforms in these services.

Reform of demand-led high needs services has to come through financial stability provided by central government. PSTs would help enable these much-needed reforms, by making it clear that central government is directly responsible for funding these services.

PSTs can build on existing ideas for reform. For example, in children’s social care, the government is piloting two Regional Care Cooperatives, which are designed to improve commissioning by pooling children’s social care budgets regionally, as well as promoting better collaboration with other public services such as health and youth justice. Similarly, a recent report on the SEND system proposed creating statutory Local Inclusion Partnerships to play an “overarching strategic and commissioning role” – we think that PSTs might be able to take on this proposed role.

We propose that PSTs should be given a formal ‘Duty to Collaborate’ to encourage place-based collaboration between different public services, and to enable budget pooling drawing on lessons from the Total Place pilots. We also suggest that PSTs should be required to spend at least 10% of their budget on programmes, schemes or initiatives which demonstrably encourage prevention or early intervention. This could be effectively ringfenced via the new Treasury spending category which Demos has proposed, Preventative Departmental Expenditure Limits (PDEL).

How could the government create Public Service Trusts?

We propose that the government should consult on creating three pilot Public Service Trusts in 2025, in order to test the model and learn lessons about how to ensure they work effectively, with a view to creating further PSTs from 2026 onwards. The pilot PSTs could be part of the Spending Review, scheduled to be finalised in spring 2025.

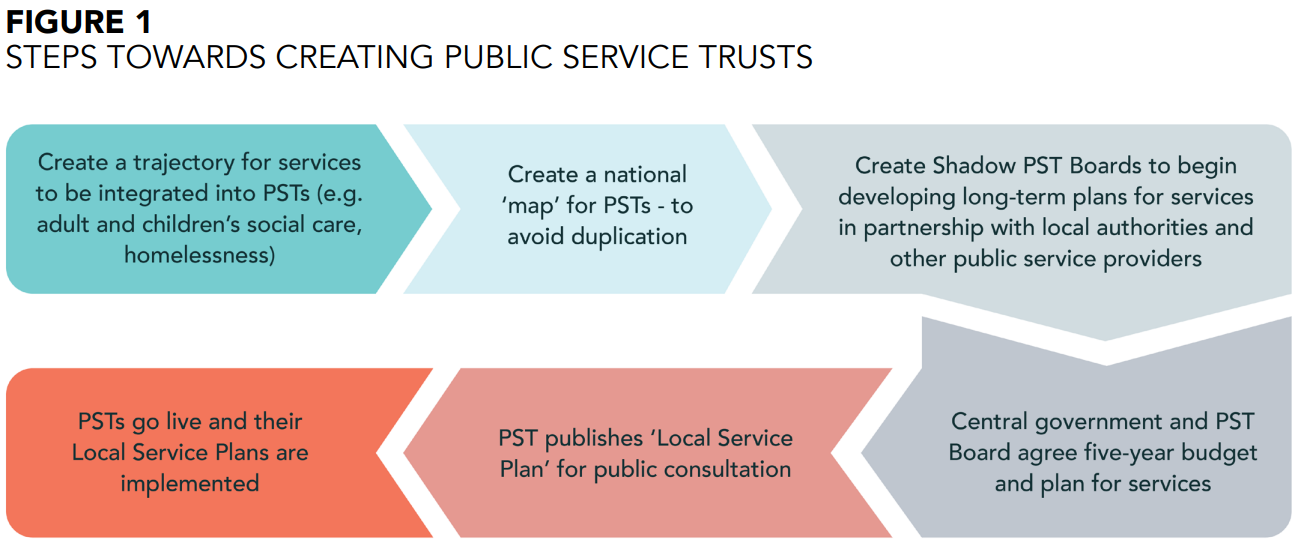

Central government, local authorities, ICBs and providers could consider the following steps in creating the pilot Public Service Trusts:

Liberated local government

We have proposed creating Public Service Trusts in order to enable local government to fulfil a new vision which we call ‘liberated local government’.

A new vision for liberated local government in England would focus on the two purposes which it is uniquely able to fulfil: local democracy and place leadership. Fulfilling the local democracy purpose means giving councils genuine autonomy so that they have the capacity and resources to respond to the priorities of local citizens – whether that is filling in potholes or funding community centres and youth services for young people. The purpose of place leadership includes building thriving local communities, partnering with and supporting charities, growing social capital and trust in local areas, providing parks, libraries, community centres and other social infrastructure, and encouraging and enabling people to volunteer in their local communities.

Demos, in our essay The Preventative State, described these kinds of policy areas as ‘foundational policy’: the social, civic and cultural spaces, activities and institutions which enable people and communities to flourish. This level of ‘foundational policy’ can help to prevent problems arising in the first place and has a significant impact on people’s overall health and wellbeing. Local government’s renewed purpose should be to provide the strong local foundations needed to improve the wider ‘social determinants’ of community strength and population health and wellbeing.

We set out more detail of our vision for liberated local government, and how Public Service Trusts could support that vision, in our paper Beyond the Sticking Plaster: A vision for long-term reform of local government finances.