Demos Daily: Received Wisdom

British politics has always had a complicated relationship with experts. Different governments have defined and redefined expert roles in their administrations, with arguments for and against technocratic policymaking filling the halls of Westminster at times of change, challenge and crisis.

At the moment, we have little choice but to rely on experts, and to place our faith in them to create policies to save lives. Yet it remains to be seen if and how this reliance on experts will shape their role in our political future. Back in 2006, Demos argued for a new approach to expertise, a new social contract between experts and society, where trust was placed in the public as often as it was demanded from them.

Read an extract from Received Wisdom, by Jack Stilgoe, Alan Irwin and Kevin Jones below, or the full report here.

Putting the politics back into policy

“Facts alone are wanted in life. Plant nothing else, and root out everything else.”

Thomas Gradgrind in Hard Times (Charles Dickens, 1854) (1)

Dickensian London was a pretty unsavoury place. Economic growth in the first half of the nineteenth century had brought thousands of new people to Soho, but the sewers for which we now thank the Victorians had not yet arrived. Cholera flowed freely through the city. Bodies were regularly carted down the narrow streets. In 1854, one epidemic was particularly virulent, posing a challenge both to experts and to families struggling to escape the disease.

London’s men of science disagreed bitterly about the cause of cholera. The prevailing theory was that it was spread in the ‘miasma’ – the foul-smelling cloud of smog that blanketed the city. Others,

including a young doctor called John Snow, disagreed. Snow reckoned that it was a waterborne disease. When the 1854 epidemic began, Snow began finding out about the disease and the social context in which it was spreading. In a pioneering example of ‘shoe-leather epidemiology’, he teamed up with a local vicar and began building a picture of the problem by knocking on doors and speaking to Soho residents. He mapped the cases of illness and worked back to a single water source – a water pump.

The pump is still there today on what is now Broadwick Street, outside a pub that has been renamed The John Snow. It is a monument to a particular sort of expertise – a tireless combination of knowledge, detective work and willingness to challenge the received wisdom. In a new book, Steven Johnson retells the story: Snow himself was a kind of one man coffeeshop: one of the primary reasons he was able to cut through the fog of miasma was his multidisciplinary approach, as a practising physician, mapmaker, inventor, chemist, demographer and medical detective. But even with that polymath background, he still needed to draw upon an entirely different set of skills – more social than intellectual – in his affiliation with Reverend Whitehead. (2)

In Hard Times, published in the same year, the hard-headed Gradgrind places his trust in the power of isolated ‘facts and calculations’. In contrast, Snow and Whitehead’s story is one of expertise-in-context. It is about exploring uncertainty, questioning authority and mixing different sorts of knowledge. And it can teach us plenty about modern expertise. In 1850s London, complexity and chaos were visible in the streets. We now take clean water for granted. But we should not pretend that our problems have disappeared. Johnson draws a direct connection from John Snow to bird flu. As London was coming to terms with being a global city, it was taken by surprise by new epidemics. Now, diseases born continents away can appear on our doorstep within hours. And we don’t yet know what it would take to make them dangerous.

Presented with a new threat, it is clear that certain sorts of expertise will be necessary. Understanding bird flu will require the knowledge and wisdom of epidemiologists, geneticists and pathologists. But it is not clear which sorts of expertise will be sufficient. Nor is it clear how we should make the best use of this expertise. In this pamphlet, we have narrated the first steps towards an open model of expertise that should make us more resilient to such surprises.

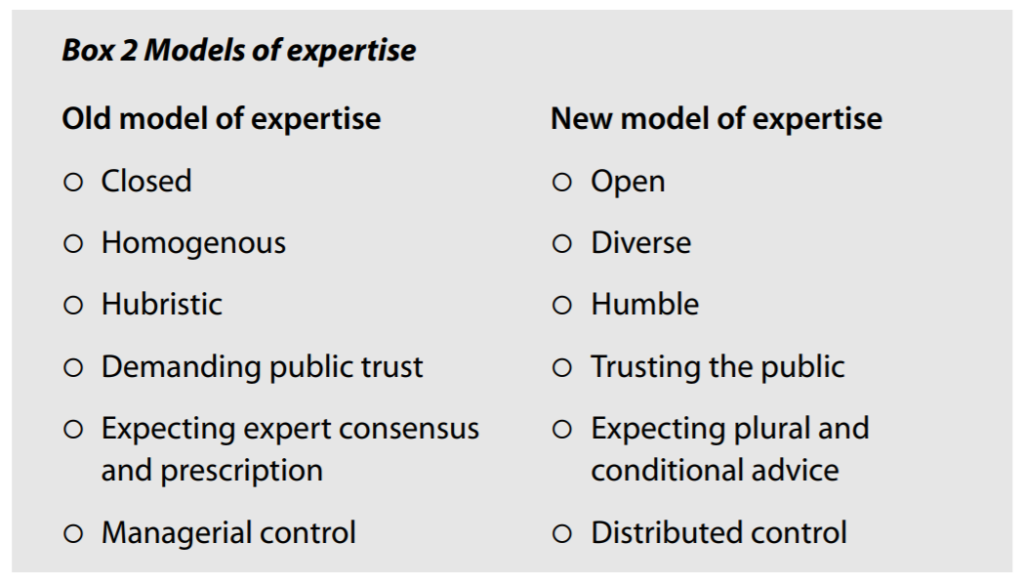

We cannot offer a blueprint for this new model. A new social contract between experts and society will be the product of ongoing discussions between individuals, cultures and institutions. But we can offer some pointers to the issues that will become more relevant as this new model is debated and retooled. Box 2 below gives a sense of what this model needs to look like and what our new expectations of experts should be.

We have seen that government is taking steps towards this new model. Newer organisations such as the Food Standards Agency are further along this road than most. But even the stubborn culture of central government is changing. At Defra a senior official told us that, in its journey to a more open approach, ‘the ship has turned 75 per cent in the right direction’. In other departments, the words have changed, but the body language has remained much the same. And some new bodies, such as NICE, are finding it hard to reconcile their public desire to listen with their backstage machinery of cost–benefit analysis.

This pamphlet has asked what still needs to be done. Responsibility for the necessary changes to expert advice cannot just be placed at the door of experts, nor just at the door of policy-makers. Instead, we must change the way that expertise and policy talk to one another. The relationships in the system are as important as the individuals. To embed a new model of expert advice, we now need to extend our thinking towards some areas that ten years ago would have been unimaginable, and may still seem counterintuitive and uncomfortable.

Read the full report here.

Notes

(1) Quoted in Irwin, Citizen Science.

(2) S Johnson, The Ghost Map – The story of London’s deadliest epidemic – and how it changed the way we think about disease, cities, science, and the modern world (New York: Riverhead, 2006).