Demos Daily: Building Companionship

The lockdown is perhaps the most important thing we can be doing to stop the spread of Covid 19, but it’s brought its own challenges, particularly for those at risk of loneliness or mental health issues. Fighting loneliness is increasingly at the forefront of public policy, and the government has already committed to attempts to reduce its effects. However, there’s now an urgent need to refocus these efforts, as those most at risk are often those with health conditions and the very elderly, who have been asked to continue to shield at home. An important, if often overlooked aspect of the conversation is how the type of housing people are living in has a clear effect on their experiences.

In 2016 Demos produced Building Companionship, looking at how to reduce loneliness later in life, and specifically how good quality retirement housing can make a real difference for those who live in it.

You can read the full report here, or the executive summary below.

Executive Summary

Context

This report explores the issue of loneliness in later life: the scale and nature of the problem; the impact on health and potential costs to the state; what is most effective in combatting loneliness for older people; and, importantly, why it might be that older people living in specialist age specific housing (retirement housing, extra care, assisted living and so on) tend to feel far less lonely than their counterparts in general housing. Demos is carrying out this work with the support of McCarthy & Stone, the retirement housing provider, to better understand how loneliness can be tackled and what factors of retirement housing contribute to older people feeling less lonely and building better social networks. For this report, Demos reviewed the evidence regarding loneliness in later life, interviewed a small

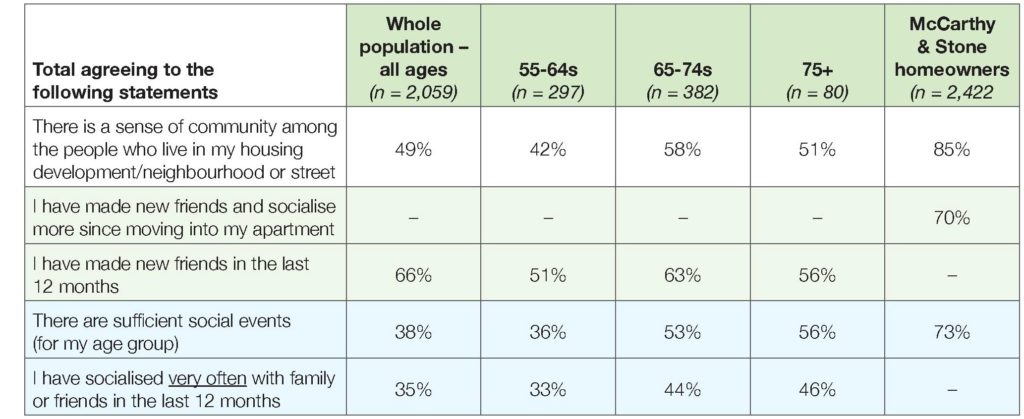

number of McCarthy & Stone homeowners about their social lives before and after moving into retirement housing, and commissioned a survey of the public – the findings of which we directly compared with a survey McCarthy & Stone has recently carried out with their homeowners where some of the key questions related to social networks and companionship. McCarthy & Stone are interested in to what extent, and why, older people are less lonely in retirement housing, and whether lessons might be learnt for wider aspects of policy, such as neighbourhood planning – to help older people become more socially connected and feel less lonely regardless of where they live.

Tackling loneliness

Evidence suggests loneliness is a large and growing problem among older people, and particularly so for the older old (i.e. over 80s). Risk factors associated with a greater sense of loneliness include poor health, living alone, being widowed, and having limited social, civic and cultural networks. All of these risks tend to increase with age. As such, people over 80 are almost twice as likely to report feeling lonely most of the time compared to their younger counterparts (14.8% of 16-64s report this, compared to 29.2% over the over 80s).1

The impact of loneliness on one’s health is significant and well documented – from poorer mental health to a greater risk of falling and hospitalisation. This, in turn, has obvious cost implications for the NHS, social care and wider economy, though no one has yet quantified the country-wide “cost” of loneliness in later life. However, schemes which have sought to tackle loneliness on a small scale have consistently shown a positive impact and associated cost savings in reducing falls and hospitalisations, to the tune of around £3 saved for every £1 invested in reducing loneliness.

The most effective interventions to tackle loneliness among older people tend to have three things in common – they work on a group basis, they focus on a common interest or activity, and they allow for the involvement of older people in their planning or implementation.

Housing and loneliness

Older people living in specialist age-specific housing (such as retirement housing and extra care assisted living developments) tend to report being less lonely than their peers. For this report, we compared the findings of a large survey of McCarthy & Stone homeowners with a survey of the general public asking comparator questions. The findings are conclusive – McCarthy & Stone homeowners (whose average age is c.80) are much more likely than older people in general to say they have socialised recently, to report feeling a sense of community, and to say there are enough social events for them to enjoy.

There are a variety of explanations for this – for example social engagement in retirement housing developments tend to have the three features of successful schemes to combat loneliness, outlined above. However, the evidence also points to the importance of shared and communal space and facilities to encourage social engagement, as well the design of retirement housing which promotes mobility and better health (enabling older people to leave their homes and socialise in a safer way) and less time spent on maintenance (allowing more time for socialising and leisure). The factors present in retirement developments could be described as either “people” (an inclusive community ethos and pro-active staff and homeowners who encourage other to participate and arrange activities) or “place” (the design of communal space etc).

Implications for policy makers and practitioners

Implications for policy makers and practitioners

Tackling the growing problem of loneliness among older people is both a social and economic priority – the implications for spending on health, care and support services for socially isolated older people, at a time where budgets are already stretched, are such that the case for preventative and lower level “social fixes” to tackle loneliness (and its health implications) is compelling. The recommendations in this report consider how policy makers and practitioners might learn from the common features of the most effective housing-related interventions in tackling loneliness, but also how the features of specialist retirement accommodation – where older people report to be far less lonely – might be encouraged more widely. Many older people are interested in a move to age-specific housing developments (certainly with demand outstripping supply),2 though it is far from the case that such housing would be able to meet the needs of all older people, particularly as many older people will want to stay in their current family home for as long as possible. As such, it is important to consider what we might learn from what can be achieved in housing developments and apply this even more widely to neighbourhood planning.

Recommendations

- Apply a “city for all ages” approach to neighbourhood planning and Local Plans, including sufficient age-appropriate housing, communal space and transport to enable older people to remain socially, physically and mentally active

- Create older people’s “social agents” to encourage active citizenship among older people to encourage people to socialise and engage in activities

- Recognise the health and care costs associated with loneliness and isolation in Joint Health and Wellbeing Strategies and develop commissioning strategies which might tackle this social issue as a public health challenge

- Bring local businesses on board to create opportunities for older people to meet and socialise – in particular retail, hospitality and leisure

- Ensure the Digital Inclusion Strategy and local schemes recognise the internet as a social vehicle and gateway

- Encourage local authorities and housing schemes to develop a social media presence for older people to develop social networks

- Help ensure demand for retirement housing is met – by helping older people to access retirement housing, loneliness and isolation might also be reduced

- Ensure retirement housing developments have the right design and ethos to create sociable communities, based on the evidence of good practice

- http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20160105160709/http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/dcp171766_418058.pdf

- Wood, C; Top of the Ladder, Demos 2013