Demos Daily: A Good Retirement

The retired and those living in retirement or care homes are facing unprecedented challenges. All have found their daily lives severely curtailed, with no visits from family and friends to look forward to. Until recent figures were released, the huge number of people losing their lives in care homes as a result of Covid-19 was also largely unrecognised. This comes amid an ongoing crisis in the provision of social care, with an ageing population increasing the cost of care at an unsustainable rate. In 2017 Demos asked what really mattered to people when they retired. We found health was a top priority alongside financial security.

Read A Good Retirement here, and see our recommendations for making the care system work for all, and what the government could do to prepare us all for retirement.

Executive summary

Demos carried out research during the summer of 2017 to get a better sense of how the public viewed their responsibilities in later life. We focused on the following questions:

- What do people define as a good retirement?

- How confident are they that they will achieve this?

- Who is actually responsible for achieving a good retirement – the

state or the individual? What combination of the two? - How can a good retirement be achieved?

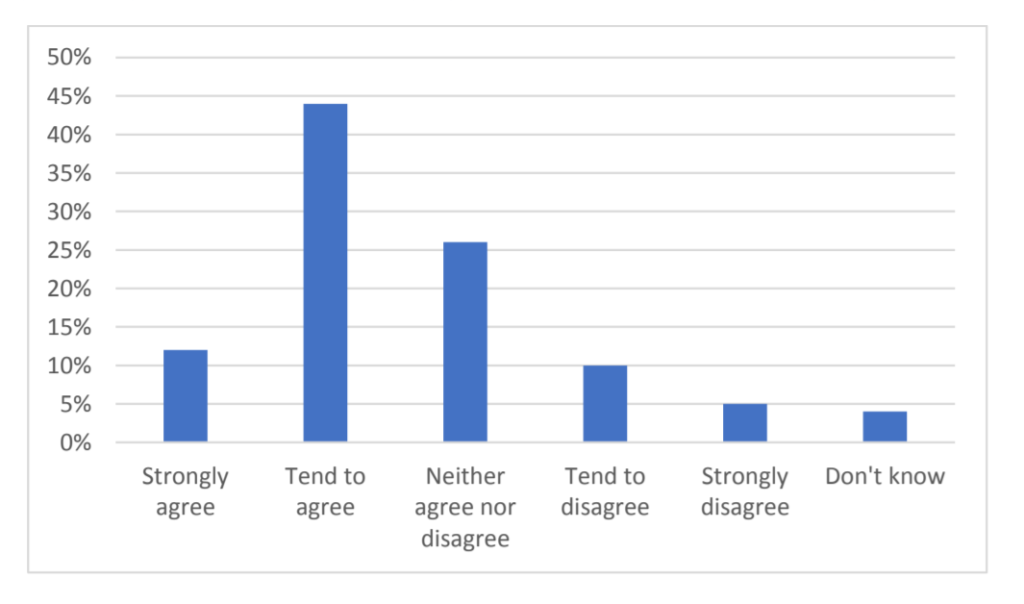

Our research, including a survey of around 2,000 members of the general public as well as focus groups with people over 40, showed that people value health and financial wellbeing in retirement, and believe the government should provide a safety net of some sort, but most tend to agree that wellbeing in late life is a matter of individual responsibility (figure 1).

Figure 1 The extent to which survey respondents agreed with the statement ‘It should be my responsibility to save so that I can pay towards the costs I will face in my retirement’

Social care can have a considerable impact on both health and financial wellbeing in later life – making it one of the key factors in determining the quality of one’s’ old age. We, therefore, paid particular attention to social care – a live policy debate in summer 2017. Again, most of the public believe that paying for care is a matter of individual concern, though expect the state to provide some form of safety net – whether to ensure the poorest have access to free care or that no one pays an excessive amount.

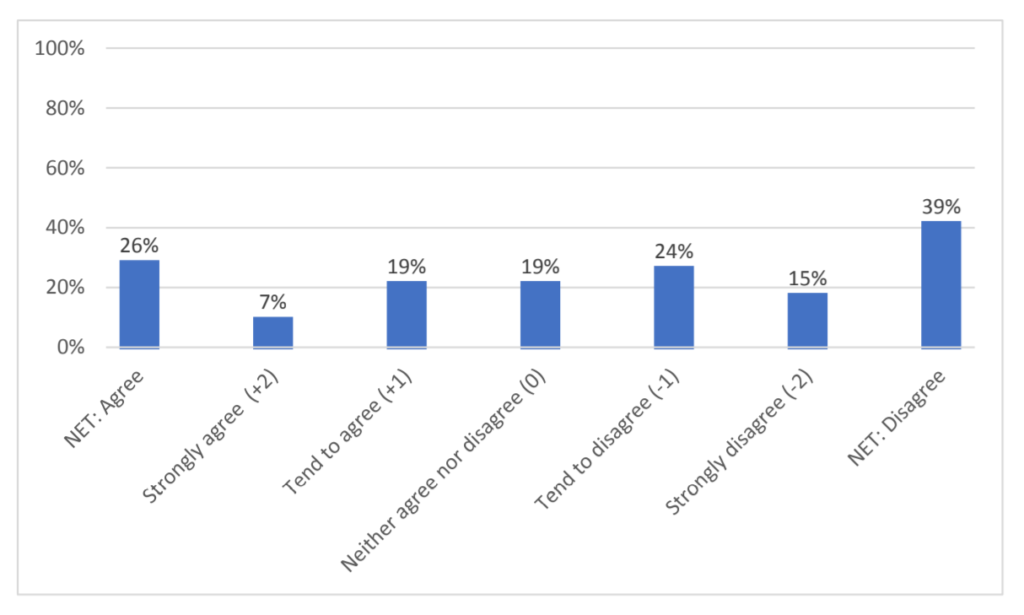

The number of people who believe that it is an individual’s responsibility to pay for one’s care appears to be growing with time. However, few people are actively preparing to meet their potential social care costs, and a quarter of the public remain complacent and assume the government will provide care free of charge (figure 2).

Figure 2 The extent to which survey respondents agreed with the statement ‘If I need to use care and support services in the future, these will be free’

This report discusses how to square this circle. The government has announced there will be a care green paper and consultation on a funding model in 2018. Alongside developing a state ‘safety net’ model (whether through a care cap or some other variant), the government now has an opportunity to implement a strategy that:

- is open and clear about what responsibility the state will take on,

and what is expected of the individual - enables older people to fulfil their individual responsibility

Our research suggests that most of the public say they will either ‘save up’ or ‘downsize’ (use their housing assets) to pay for care in later life. And yet we know that very few people save regularly – it would be almost impossible for most working-age adults to save enough to pay for their potential care bills. We also know that most older people resist moving home for practical, emotional and other reasons. With this in mind, it is clear that saving up or downsizing are not viable strategies for paying for care in and of themselves, but rather need to be leveraged through the use of financial products. The government can help people

fulfil their individual responsibility in paying for their care in later life by ensuring they engage with financial products – variants of insurance and equity release products can make a reality out of the public’s instincts to ‘save up’ or ‘use the house’. The government may simply invest in more provision of advice to improve understanding and take up of such products (‘demand side’ stimulus), but it may also help supply by developing suitable products in partnership with the financial services sector, actively encourage their use or, potentially, underwrite or (co)deliver such products itself.

We recognise the shift in political and policy thinking regarding the cost of an ageing society. Years of ring-fenced spending on pensions and older people’s benefits is drawing to an end, in the face of pervasive and ongoing cuts to working age services and benefits. An age of greater individual responsibility is upon us, and all the indicators suggest that soon almost everyone will have to pay for their care in later life, subject to a limited safety net. We conclude by explaining that this does not divest the government of all responsibility – on the contrary, the government has an important task ahead in preparing people for this

shift.