Global Britain vs Little England

Since the EU Referendum, Boris Johnson has ramped up the rhetoric about ‘Global Britain’, a country that is “more open, more outward-looking, more engaged with the world than ever before.” In this view, the referendum result is a vote for free trade and international enterprise, free from the constraints of EU trade policy. There seems to be a tension here with the core of the Leave vote, which was widely seen to represent a vote against globalisation, against immigration and for protecting UK markets. A new project by academics at the University of York, in collaboration with Demos, will shine a light on public attitudes on trade after Brexit. The first tranche of findings (available here) suggests that, somewhat paradoxically, Leave voters are in favour of Global Britain and opposed to globalisation.

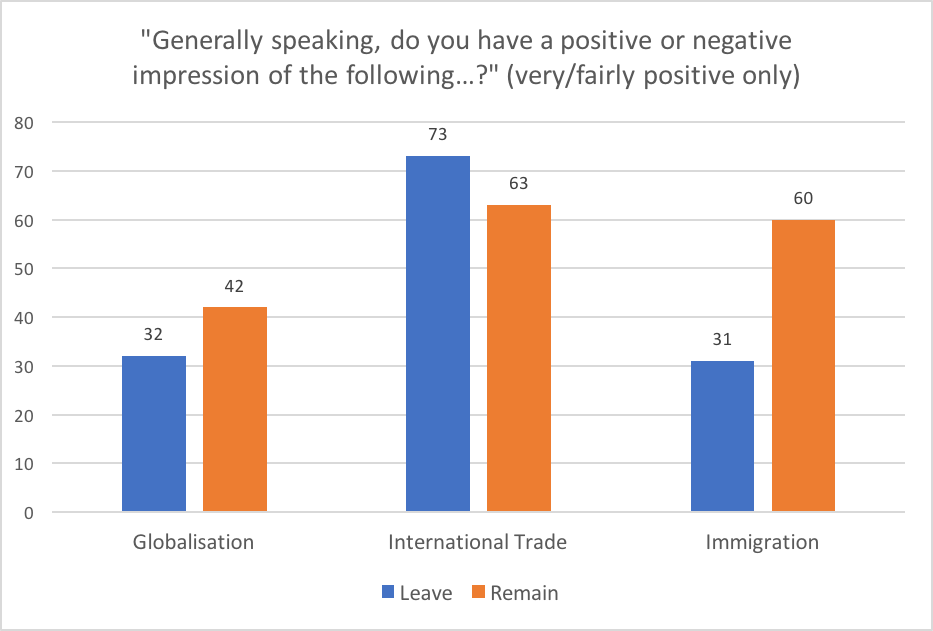

Here is what we found: in line with expectation, Leave voters tended to respond more negatively to words such as globalisation and immigration. Does this mean the Global Britain framing had no basis in reality? Not quite. Leavers were more likely to hold a favourable view of international trade (at 73% favourable among Leavers, compared to 63% for Remainers), despite being less positive about globalisation overall (32% compared to 42%).

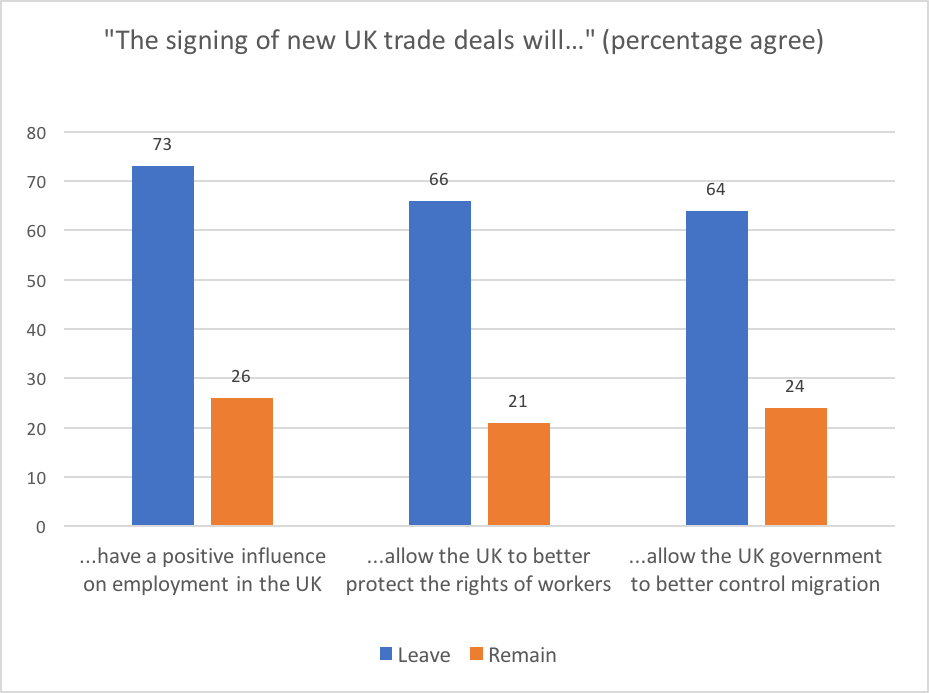

What explains the disparity? Mainly, Leavers tend to believe that new trade deals will leave the UK better off. 73% of Leavers believe new free trade agreements (FTAs) will be good for employment in the UK, even though academic research suggests that Leave voters were disproportionately clustered in areas experiencing fierce trade competition. Leave voters also tend to believe FTAs will allow the UK to better protect the rights of workers (66% of Leavers agree) and allow the UK to better regulate the safety and quality of goods and services (73% agree). For Remainers, it’s roughly the reverse.

Leavers and Remainers differ so much on trade attitudes precisely because they have very different views on what the UK stands to gain (or lose) from trade. In part, this may be an expression of Brexit partisanship. But it is also a genuine difference in both groups’ assessment of the strength of the UK’s negotiating position. Our survey asked participants to rate the UK’s strength in trade negotiations vis-a-vis prospective trading partners, where a score of 1 means the UK has the upper hand and 11 means the prospective trading partner has the upper hand. In general, the US is thought to have the strongest hand and India (!) the weakest, behind countries such as Australia, Canada and Japan. Leavers tend to be much more optimistic about the relative strength of the UK in these hypothetical negotiations.

This creates a difficult situation where Brexit voters are very positive about the idea of free trade, while denouncing any trade-offs a deal would likely involve. It is legitimate to seek new trading arrangements for Britain. Perhaps we decide that lower product standards are an acceptable price to pay for cheaper goods and services. Perhaps we are happy to receive more immigration from, say, India in exchange for a wide-ranging trade agreement. But when politicians and the public deny the existence of trade-offs, disappointment is sure to follow.