Our new immigration system needs flexibility, transparency and public support

We’re about to leave the EU and, unless the transition period is extended, the Government has less than a year to put a new immigration system in place. It’s setting up a system ostensibly to address public concerns, and turning Priti Patel’s hard talk into tough action.

But employers are worried and have been making their voices heard. The Government will have to navigate a difficult course if it wants to tighten restrictions without damaging the economy. The new system will allow lower skilled migration to continue only through short-term visas. These will be initially restricted to a few sectors, for example agriculture, but economic necessity will mean they will have to be extended. Fearing negative public reaction, the Government is likely to do this through exercising in-built flexibility and stealth rather than overt policy change.

Those who expected to lower skilled migration to end may feel let down. And an increase in temporary over longer-term migration may be unwelcome in some communities. But instead of setting up a system which will fail and corrode public trust, wouldn’t it be better to take account of public attitudes now? As existing research shows, these are much more nuanced, less ideological and more realistic, than the architects of the new policy assume.

Hardline policies are likely to be tempered by pragmatism

The Conservatives have always made it clear that the new, post-Brexit, immigration system will prioritise the ‘brightest and best’, a term repeated tirelessly by past and present prime ministers and home secretaries. In line with this emphasis, the Conservative plan for immigration includes three broad tiers – exceptional talent, skilled workers and ‘sector-specific rules based’. This third tier is currently a poorly defined mix of temporary low skilled visas, youth mobility or short-term visits. Crucially, these visas will be ‘time-limited’ and will not offer a route to settlement, while higher skilled visas will.

Further details of the new policy will follow delivery of a report from the Migration Advisory Committee (MAC) this month. The MAC will not only influence the new policy but play a more direct role than previously in its adaptation and reformulation. There will be an annual reassessment of the points system, based on MAC’s advice, ‘so it can be adjusted according to changing economic or social circumstances’. And in anticipation that employers will need to recruit lower skilled migrants, the composition of the lower skilled tier ‘will be revised on an ongoing basis based on expert advice from the MAC’.

The MAC is run by labour market experts who listen to employers and are aware of the value of migration to employers and the economy. They are unlikely to ignore the reality, that sectors such as social care, food production and hospitality will need the flexibility built into the new system. If the Government takes advice from the MAC, sectors thrown into crisis through inability to recruit local labour may be given concessions and allowed to issue visas. There will also be pressure to give concessions beyond highly skilled migration to countries negotiating Free Trade Agreements who will want to include immigration in their deals. Tough talk may need to give way to expediency for Brexit to look like a success.

What might the public support?

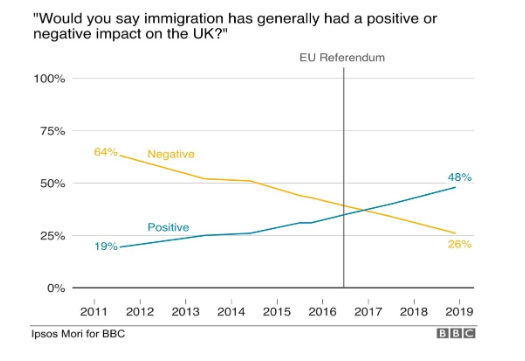

Opinion polls have consistently found that the British public would like to see immigration to the UK reduced. Yet, as Ipsos Mori surveys have found, attitudes have changed. More people are now more positive than negative about the impact of immigration. It’s not clear if this is what some have called the ‘galvanising’ effect of Brexit – we’re leaving the EU and free moment is going to end – or that all the talk about immigration led has drawn attention to its benefits. Given Brexit uncertainty, the second explanation seems more likely.

Surveys have more consistently found opposition to low-skilled migration and support for high-skilled migrants, appearing to endorse the new restrictions. However, these findings may have been misinterpreted, by relying on the assumption that respondents interpret ‘high’ and ‘low’ skills in the same way as the government. People are certainly baffled that a nurse or teacher might not qualify for a skilled visa, for example. But also view care and construction workers as skilled workers the UK needs.

In-depth qualitative research suggests that high-skilled migrants are often interpreted as shorthand for migrants with a large contribution to the economy through paying taxes and filling skill gaps. The public recognises the value some low-skilled migrants bring, by filling vacancies in hard-to-recruit sectors. They want migrants who come to work or to study. They worry that some migrants come to commit crime or claim benefits, not that they work in low skilled jobs.

And what of short-term visas allowing stays of up to 12 months? According to the ONS, only 1 in 5 migrants who come to the UK for employment stay for less than a year. They are much more likely than longer stayers to work in London and the South East. Fruit pickers aside, few communities have experienced significant short-term inward migration. This could change quite dramatically under the new policy, as will use of agencies and temporary accommodation. Unable to bring their families, new migrants will be young, single and transient. And this will be very visible to communities accustomed to more settled migration. On short-term visas alone, the government should be cautious and listen to the public.

Taking account of public attitudes will prevent backlash when controls need to be relaxed

The current proposals are highly restrictive, especially for lower skilled workers. Flexibility will have to be exercised to prevent damage to the economy, especially faced with wider Brexit challenges. Existing research tells us that the public would accept a more liberal regime than the Government has in store. This makes it possible, as well as desirable, to change policies through public support rather than stealth.

Through systematic, in-depth and mixed methods research, the public could be engaged on the principles of new immigration policies, but also some of the details, about sectors, skills, short-term stays and settlement. These are the issues that affect people most, as consumers of goods and services and as citizens. The process must involve experts and evidence so that research participants are able to consider the options in an informed way. Very little research on public attitudes towards immigration is being commissioned and few funders other than the government have the resources for work of the scale needed.

Without public engagement using indepth research methods, immigration policy is likely to be ill-conceived and damaging to communities as well as to the economy. The Government has less than 12 months to create a workable system. To make it work for everyone is a challenge. But failure to listen to the public on the most central Brexit issue will further corrode trust in politicians and widen social divides.